Women and men on the plantations

There was a strict social order on the plantations. The white owner or his white manager was at the top of the social structure. Below him were other white employees, such as overseers and book keepers. Amongst the black slaves, skilled craftsmen such as carpenters or sugar boilers ranked above ordinary field slaves. At the head of the field slaves were men and women known as drivers, who were supposed to keep the field slaves hard at work, by use of the whip if necessary. Those slaves chosen to work in the house were considered to be of higher status than the field slaves. It could be a terrible punishment for a house servant to be put with a field gang to do heavy field work after the lighter duties in the house. There was also an order based on colour. The blackest slaves usually had the hardest work. The lighter-skinned slaves, often the children of the owner or manager by a slave woman, were often given the better jobs, kept as house servants or trained in a skilled job.

Some slaves worked in the towns, or as boatmen. But the majority worked on the plantations, for 12 hours or more a day. Plantation work required many hands. Sugar especially was labour-intensive, and everyone was expected to work, even old slaves and children. Work on a plantation depended on the crop grown. The cultivation and processing of sugar, for example, required different skills from those needed for rice or tobacco. There were skilled jobs which Africans did: such as carpenters, coopers, blacksmiths, potters, sugar boilers. These jobs usually went to men. Women were mainly confined to fieldwork, though some worked as house slaves.

More men were brought from Africa as slaves than women. But some plantation owners preferred women as the harder workers. The ‘great gang’ or first gang of slaves was made up of the strongest workers. Sometimes women outnumbered men in the great gang. They did all the heavy fieldwork, such as digging and cutting cane.

The members of the second gang were not as strong as those of the great gang. Often the slaves in this gang were the teenagers, the old and the sickly. They would do the less demanding fieldwork.

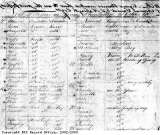

Slave owners kept lists of their slaves and animals. The Spring Plantation in Jamaica was owned by the Smyth family, from Ashton Court in Bristol. Pictured here, is an account from the Spring Plantation business papers, which lists the 93 slaves owned by the estate in 1785. The name, occupation and condition of each slave is given. Some are ‘Able’, that is in good health and able to work. A large number are noted as ‘Old & Weak’ or ‘Old & Sickly’. One, called Kitt, is noted as an ‘Able Man Boy’, presumably a young teenager. The jobs listed include mason, cook, washerwoman, house wench, ‘Cook for White People’, cooper (barrel maker), carpenter, watchman, cattleman, ‘Driver to Small Gang’ or the head of the children’s gang, ‘Hog Boy’ (looking after the pigs), waiting boy (in the house), driver (head of a gang), field hand and distiller.

Marriage between slaves was discouraged until the late 18th century, although many slaves formed relationships and had children. Often the relationship was with a slave from a neighbouring estate. Plantation owners were known to order a husband or partner to flog his own wife for an offence. If the slaves were owned by different estates, that could not happen. Slave women were routinely raped by the white men on the estate, by their owner or by the white supervisors and employees. Some women were forced to use sexual favours to white men simply to survive or to obtain better conditions, even freedom, for themselves or their children.