God(s) on the plantation

One way the enslaved Africans had of resisting their enslavement was to keep alive their African culture. In personal names, customs, music, stories, food and beliefs, the slaves could preserve their identity as Africans and be disrespectful to their European owners. African religious beliefs were kept alive in the Caribbean and the Americas. Sometimes, African beliefs were merged with Christian belief. The best-known example of this mixing of religions is the vodou religion found on the Caribbean island of Haiti. Here, African beliefs were mixed with the teachings of the Catholic Church. Vodou has been written about as an exotic and dangerous pagan (or ‘heathen’) religion, but few outsiders have understood this mix of Christian and African belief.

The Africans shipped across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas were taken away from their traditional culture and sold into a new culture. They were able to keep parts of their traditional culture alive, and adapt it to their new circumstances. The enslaved Africans of different ethnic groups and cultural traditions could work together to create new ceremonies, a mix of all their beliefs, for burying the dead, naming children and other important occassions. Morgan Godwyn, a clergyman writing in the 1680s about the island of Barbados, referred to the ‘certain Figures and ugly Representations’ of gods which the slaves made and kept in shrines for worship. The dead were often buried with food and drink, which was thought to sustain them on their journey into the afterlife. They were probably also buried with other objects which would identify the dead person to their relatives in the afterlife. It was believed that the dead person would return to Africa, as long as their body was intact. The European plantation owners could use this against the enslaved Africans. As a threat, punishments could involve mutilation of the body, cutting off the toes of persistent runaways, for example. This was feared by the slaves as they thought it would prevent their spirit from returning to Africa after death. As in so many parts of Africa, the ancestors were deeply respected. On the island of Antigua in the Caribbean on Christmas Day, because that was given as a day off, the slaves would visit the graveyards and make offerings of food and drink at the graves of their relatives.

Amongst the African men and women sold into slavery there were those who had specialist knowledge of all things sacred. These were priests of various gods, and herbalists (people who knew about herbs and their properties). These people were held in great esteem by the slaves on the plantations. Europeans usually referred to all of them under the one term Obeah, which they confused with witchcraft. The Obeah men and women grew from the overlapping of jobs, such as herbalist, diviners, witch doctors, and mediums. They diagnosed and treated illness, obtained revenge for injury, cured the bewitched, found out and punished theft and adultery and predicted the future. They were feared by the white plantation owners, for their power over the slaves, their association with slave rebellions and their knowledge of poisons.

On British colonies, the attitude to Christianity was mixed. Many slaves believed that being baptised as a Christian would make them free. They thought this because a Christian could not be a slave. For this reason plantation owners often discouraged Christian preaching, as it gave their slaves ideas above their status.

But Christian missionaries did work on the Caribbean islands, preaching and converting slaves. Some white people disliked the missionaries for other reasons. One Samuel Augustus Mathews of the island of St Eustatius seems to have disapproved of the Methodist Church and the effect that their preaching had on the slaves. “ “if the British Paliament” he wrote in 1793, “had, in their great wisdom, prohibited the exportation of Methodist Preachers into the West Indies, thousands of those poor deluded wretches would now be in the land of the living who have died terrified with the idea of Hell fire and flames”.

The churches did work on the Caribbean islands, sometimes with the permission of the plantation owners, sometimes without. On the British islands it was mainly the evangelical churches which sent missionaries out to the slaves. The Baptist and Methodist churches had many converts amongst the slaves. Religion could provide a way for the slaves to organise and educate themselves. It gave black leaders a training in organisation. It gave the slaves a hope of something better after death.

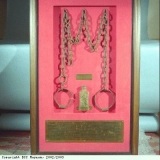

Church leaders and missionaries were not always popular with the supposedly Christian plantation owners. William Knibb was a missionary from the Broadmead Baptist Church in Bristol. He went out to the island of Jamaica in 1824. The slave trade had been abolished but slavery itself continued on the plantations. He saw the cruelties of the system. Knibb became a champion of the slaves, fighting their cause. The preachings of the Baptist Church about freedom were blamed for a major slave uprising in Jamaica, called the Baptist War, in 1831. Rumours of impending freedom for the slaves encouraged the rebellion. The Baptist War was brutally put down by the British authorities in Jamaica. Over 300 rebels were executed. Knibb himself returned to Britain to campaign for the end of slavery. He was an inspiring speaker and travelled the country preaching against slavery. He is said to have used these slave chains in his speeches, showing the conditions under which slaves lived and worked.