Identity in the Caribbean

The transatlantic slave trade took people to the other side of the world, from Africa to the Americas. For enslaved Africans taken by the Europeans there was no hope of ever returning home. Men, women and children were expected to work for their entire lives with no freedom or rights. The slave owners did everything they could to make sure that the enslaved Africans forgot their languages, cultures and religious beliefs.

The enslaved Africans did all that they could to resist their enslavement. From the moment of capture and the journey across the Atlantic Ocean, to the plantations, enslaved Africans rebelled. Even in the knowledge that they would never get back to their countries or achieve freedom, they persisted in their resistance. Resistance took many forms. The enslaved Africans could purposefully damage machinery, work slowly or openly rebel against their masters and their slave status. They could also resist in subtler ways, for example, by keeping alive their African religious beliefs, names, language, music and stories. Pictured here is a drum from the Caribbean island of Haiti. The African slaves on Haiti fused their African religions with their French owners’ Catholic religion, and created their own form of Christianity, called vodou. This meant that they managed to practise their own mix of beliefs from different African religions, whilst seeming to their owners to be practising Christianity, as instructed. Drums like this were made and used in the ceremonies of this new form of religion in Haiti.

The Maroons were escaped slaves. They ran away from their Spanish-owned plantations when the British took the Caribbean island of Jamaica from Spain in 1655. The word maroon comes from the Spanish word ‘cimarrones’, which meant ‘mountaineers’. They fled to the mountainous areas of Jamaica, where it was difficult for their owners to follow and catch them, and formed independent communities as free men and women.

As the Maroon population grew through new runaways, the Maroons were seen as a constant threat by the Jamaican government. The British fought two wars to bring the Maroons under control, the first from 1728 to 1739, and the second from 1795 to 1796. The First Maroon War ended when the British realised that they could not defeat this enemy, and so made a peace agreement with them. The freedom of the Maroons was recognised and their land was given to them. The Maroons were to govern themselves. In return they would support the British government in Jamaica against foreign invasion and would help capture rebel slaves and runaways from the plantations and return them to their owners.

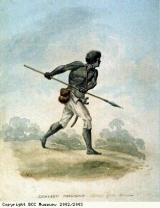

The Second Maroon War started when, in 1795, the new Governor of Jamaica, Balcarres, decided to deal with some minor breaches of the peace treaty by the Maroons who lived in Trelawney Town. The plantation owners were against another war, wanting a negotiated agreement with the Maroons to maintain the peace. After five months of fighting, the undefeated Maroons were offered an agreement for peace. The Governor then cheated on the peace agreement offered. The Maroons were arrested and, against the agreement they had accepted, were transported off the island to Nova Scotia, on the east coast of north America, and later went to Sierra Leone, West Africa. Leonard Parkinson, pictured here, was one of the leaders of the Maroons in the Second Maroon War. The local authorities put a price on his head of £50, (about £2,500 today), wanted dead or alive.

Few people realise that the slaves themselves fought for their freedom and in fighting helped to win it. In Britain, the trade in slaves was ended in 1807, by a law for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. In 1833, an act was passed which abolished slavery itself. These legal acts were brought about by a combination of events. Activists (black and white) campaigned for the slave trade and slavery to end and influenced public and political opinion. Combined with the continual resistance of the slaves themselves, and the change in opinion back home about slavery, abolition and emancipation eventually came. Often, the role of the campaigners in Britain is seen as the only reason for the end of the slave trade and slavery. In reality, the problems caused by the slaves themselves were a severe threat to the continuation of the slave trade and to the economic viability of plantations.