District of St Pauls

A modern urban myth has arisen about the St Paul’s area of Bristol. In the 18th century St Paul’s was a fashionable suburb of Bristol. A well-off merchant lived in one of the houses in the very smart Brunswick Square or Portland Square. The merchant quarrelled with his neighbours, and to spite them he left his house to his black servant when he died. The servant married and had children, the neighbours moved out and black friends of the servant moved in. Over time, the wealthy white residents all moved out, the houses declined and the area was no longer a fashionable place to live. Thus in the 1950s, the new migrant black families found a welcome in the St Paul’s area because it was already an area with a high proportion of black residents.

The facts are slightly different. St Paul’s was indeed a very smart address in the 18th century, and by the late 19th century the area was no longer so fashionable. Small workshops had opened, making such products as boots and shoes. But, as any pre-war resident of the area will tell you, St Paul’s before the 1940s was a still a respectable residential area inhabited by white locals. It was the bombing of the Broadmead area in the Second World War that led to the departure from the area of those who could afford to move to the safer suburbs or the country. Bomb damage, planning blight and neglect meant that the housing stock declined, and so the 1950s and later migrants from the Caribbean found housing there that they could afford as they established themselves in a new country. There is no truth in the story of black residence and decline since the 18th century. This myth of the slave trade must have come into existence as a way of explaining the large black presence in the area since the 1950s. As late as 1968, 61% of St Pauls’ residents were white. There are many myths about Bristol’s slaving past, but they have all been handed down for generations: this one is a relative newcomer.

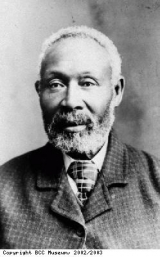

We do know of some black residents living in the area of St Paul’s before the 1950s, but they are exceptions rather than the rule. Henry Parker was a slave on an American plantation . He ran away and ended up living in Callow Hill in St Paul’s in the 1850s. He married a Bristol woman, and one of their daughters married an Irishman. Another family, the St Clairs, lived in St Paul’s in the 1930s. The husband was African-Caribbean, the wife appears to have been white. Residents of St Paul’s at that time remember no ‘colour problem’, perhaps because the St Clairs were the only black family locally and fitted in with their neighbours.

It was often felt that as black people moved into an area, they lowered the area and turned it into a ‘ghetto’. In fact, the early migrants ended up in areas already in decline because they could not find housing in better areas. And the landlords of the rundown properties they rented could charge as much as they wanted and do nothing to the houses as they knew that their tenants could not find housing anywhere else. As one Bristol public servant wrote in a report at the time: ‘Exploitation by undesirable landlords is the real problem in fading housing areas, not immigration per se.’

The riots in St Paul’s in 1980 brought the area to national attention. Sparked by a drugs raid on the Black and White Café in St Paul’s, the riot in Bristol was the first in a series of riots in large cities across the country. Contrary to popular belief the riots in St Paul’s were not strictly race riots. They were part of a long Bristol tradition of riotous action by the city’s poor against perceived injustice which date back to the early 1700s at least. In 1980, both white and black youths were involved in a protest against heavy-handed policing. There did seem to be a racial element as black youths felt that they were particularly singled out for unwarranted police attention.

The area of St Paul’s today has a reputation as the drugs and crime centre of Bristol. The police and residents are working to reduce crime and to improve the area. Although drug abuse and drug dealing is by no means restricted to St Paul’s, criminal gangs from Jamaica ( called Yardies) and a growing gun culture have, along with the spread of crack cocaine, given the area a new and unwelcome notoriety. The summer of 2003 saw armed police patrolling the streets of St Paul’s, to reassure the residents and to give a clear message to the gangsters. A turf war between local gangsters and Yardies had developed into open warfare. The gangs were armed and so the police had to be armed as well. The main victims of the violence are themselves black.

Such criminal activity makes news and is widely reported. Yet the good things about St Paul’s, the community feeling, cultural activities, the strong church presence, local action against criminal gangs, goes unrecorded.