Suppliers to the trade

It was not just the merchants and investors who were involved in the slave trade. Within Bristol and outside the city there were many people who supplied all the things needed for a year-long slaving voyage to Africa and across the Atlantic Ocean to the Caribbean.

Shipbuilders were the obvious people involved here. The slave trade needed ships. The city’s shipyards were busy places. James Hillhouse ran a shipyard in the early 18th century. He also invested in some slaving voyages. At his death in 1754 he left £30,000 (about £1,500,000 today) to his son, who carried on the business. Sidenham Teast ran the shipyard on Wapping Wharf, shown here in a drawing done in about 1760 by the captain and artist Nicholas Pocock. Teast also invested in slaving voyages, and sent ships to Africa to trade just for timber. The wood presumably ended up in the ships he built. The shipyards employed many skilled labourers, such as carpenters and sail riggers. Nearby would be the workshops of the sailmakers, chainmakers and anchormakers.

Textiles made up the largest part of the cargo taken on the slave ships for trading in West Africa. Different types of cloth, like basts and chintz, were imported from India by a trading company called the East India Company. Woollen textiles came from Devon. Later in the 18th century, striped and coloured cotton from Manchester and the Lancashire cotton mills were bought by the Bristol merchants. Highly prized goods included some items from the local industries, such as glassware from the many glasshouses in Bristol.

Other such goods were bought in from a wider area. These included umbrellas, and hats edged with gold or silver braid from London (known by traders as ‘negro hats’), beads imported from Italy and silks from India. These luxury items were used by the most powerful African traders to display their wealth and thus confirm their social and political standing. These goods accompanied the more day-to-day trade goods. Brass ‘Guinea kettles’ and ‘Guinea neptunes’ were made in the brassworks which were built beside the rivers Avon and Frome. The pots and pans were used by West Africans for cooking and for the removal salt from seawater by evaporation. Brass manillas , which served along with iron and copper rods as currency, were particularly favoured by traders in the Bight of Benin (now Nigeria). Many of Bristol’s prominent merchants owned shares in the Bristol Brass Battery, owned by Thomas and Mary Coster, including John Andrews, Nehemiah Champion, Thomas Daniel, Edward and Truman Harford, Nathaniel Hill, Walter Hawksworth, Harford Lloyd, Corsely Rogers, Joseph Percival, Charles Scandrett and William Swymmer Jr. Almost all of these men had interests in the slave trade or slave-related businesses.

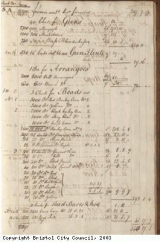

Shown here are some pages from the accounts book of the slave ship the Africa. The book lists all the goods taken onto the ship for her slaving voyages of 1774 and 1776, and their suppliers. Each slaving ship carried a large stock of trade goods bought from different merchants and shops. They also carried large stores for the running of the ship, such as food, candles, spare canvas for sails, ropes, chains, ink and paper. Ship’s biscuits were bought from Thomas Skyrme, candles from William Hughs and ropes from Smith Anderson & Co. Many others made part of their living from the Africa trade, these included makers of navigational instruments, ship’s chandlers (hardware and fittings for boats), coopers (barrel makers), apothecaries selling medicines and various small retailers who provided meat and bread to feed the crew and horsebeans to feed the enslaved Africans.

It was not only the providers of the ships, trade goods and ship’s supplies who benefitted from the slaving voyages out of Bristol. The ships needed to be sheathed with sheet copper to protect the wooden hulls from a kind of worm called the ‘teredo worm’. This was a wood-boring worm that lived in the warm waters off the West African coast. The copper-bottoming needed by ships sailing in tropical seas helped to boost the copper industry in the Bristol region.

The value of the cargo and of the ship needed to be protected against the perils of the long voyage. The insuring of slaving ships both spurred on the early development of the insurance industry and through the insurers drew in a wide range of investors in Bristol who would otherwise not have been involved in the African trade. James Rogers and Co., the owners of the slave ship the Fly, took out a special policy against ‘Negro Insurrection’ (or slave rebellion) on the ship’s 1788 voyage to Africa.